The role of the paragraph in clarifying complex scientific writing

When writing about scientific concepts or products in detail, we’re rightly focused on the words we’re using. But how often do we stop to think about how well those words are working as part of a paragraph? In this post I examine the role of the humble paragraph, and show you how to improve the clarity of your arguments with the right choice of structure and length.

Keeping track of an argument

How often do you find yourself reading a piece of in-depth science-focused writing, only to lose track of the argument part-way through a paragraph? Perhaps you took a deep breath and went through it again… or more likely you gave up and moved onto something else.

If this seems familiar, then chances are the writer didn’t consider the structure and flow of their paragraphs carefully enough. In my view, this is one of the main reasons why a considerable amount of scientific writing ends up being indigestible.

There are various ways of tackling this problem. But there’s one in particular that goes a long way to making your arguments clear first time round – the structure and length of your paragraphs.

Before we dig any deeper into this, though, let’s take a look at what a paragraph should be.

What is a paragraph?

A paragraph is, to put it briefly, a chunk of sentences. If you’re working in Word with the ‘Show non-printing characters’ toggle button on, you’ll see the paragraph endings marked with the pilcrow symbol ¶.

In novels, newspapers and other hard-copy formats where printing costs need to be kept down, a new paragraph is often indicated by an indented first line. But in most other places (and online) it’s now conventional to use a bit of white space between the paragraphs instead.

Although paragraphs can simply be used to break up the text so it doesn’t look too imposing on the page, when developing a nuanced argument or point of view, the paragraph takes on another role. It does this by allowing the reader a moment to assimilate the point you’ve just made before you move onto the next one.

As a result, using paragraphs in the correct way becomes a valuable tool to help the reader understand the argument you’re making, as they go along. But how do we do this in practice?

The paragraph as the unit of ideas

A powerful way of thinking about paragraphs is to think of them as the fundamental unit of ideas. You do this by making a statement about your idea in the first sentence of a paragraph – sometimes called the topic sentence. The rest of the paragraph then provides information that supports this statement or expands upon it.

When you’ve done this, you’re ready for the next paragraph. This could be to do one of the following:

- To further emphasise the idea

- To provide an alternative way of thinking about the idea

- To describe a consequence of the idea

- To pose a counter-argument to the idea

- To describe an alternative idea

- To answer a question resulting from the idea

- To summarise the consequences of previous ideas.

If you have lots of short paragraphs, then it’s acceptable to run them together to avoid a disjointed reading experience. On the other hand, if a paragraph has turned into a great wall of words, then it’s time to break it up. You just need to find a suitable place to do so, where you can legitimately start a new topic.

And when you start a new paragraph, it helps the reader if you indicate what’s happening. Examples of this in action are an ‘And’ (as in this paragraph), an ‘If…’ statement (as in the previous paragraph), and a question (as in the following paragraph). Such linking phrases are the glue that holds a discussion together.

Helping the reader to understand your argument

What’s the benefit of going to all this trouble? For a start, merely by thinking about the document from the reader’s point of view, you’ll have spotted places where the flow of your argument needs to be improved.

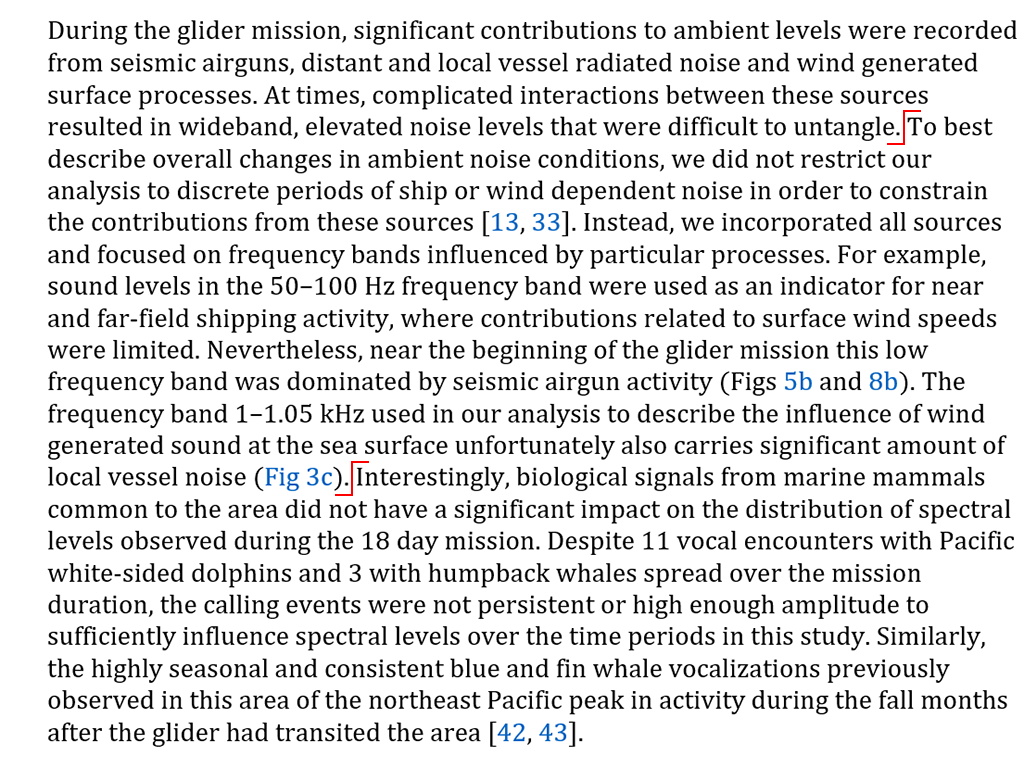

A strong paragraph structure means that the reader can get a clear idea of where the argument is going, merely by skimming down the first line of each paragraph

In addition, a strong paragraph structure means that the reader can get a clear idea of where the argument is going, merely by skimming through the article (which generally involves looking at the first line of each paragraph). This is especially useful in long documents, where it may not suit the writing style to go overboard with use of subheads.

So let’s turn to the length of these paragraphs. What should you be aiming for? Here are two rough-and-ready rules that will help keep your writing readable when explaining complex scientific concepts and data.

Rule 1: Combine paragraphs containing less than 40 words

Very short paragraphs of 40 words or less are particularly prevalent in online journalism, where it’s commonplace for them to contain just one or two sentences. For example, take this piece about climate change on the BBC site (excerpt below).

I find the experience of reading this piece disjointed and ultimately unsatisfying. This is because you’re forced to work out for yourself how the sentences relate to each other, and how they fit into the overall argument, which is exhausting work. So if you’re trying to convey a complex message, I’d recommend combining paragraphs that have fewer than about 40 words.

One caveat is that single-line paragraphs are great for grabbing the attention, and so can work well when used sparingly – but even then only really for web copy. Elsewhere they give an impression of informality that can make it sound like you’re not being serious.

Rule 2: Split up paragraphs with more than 180 words

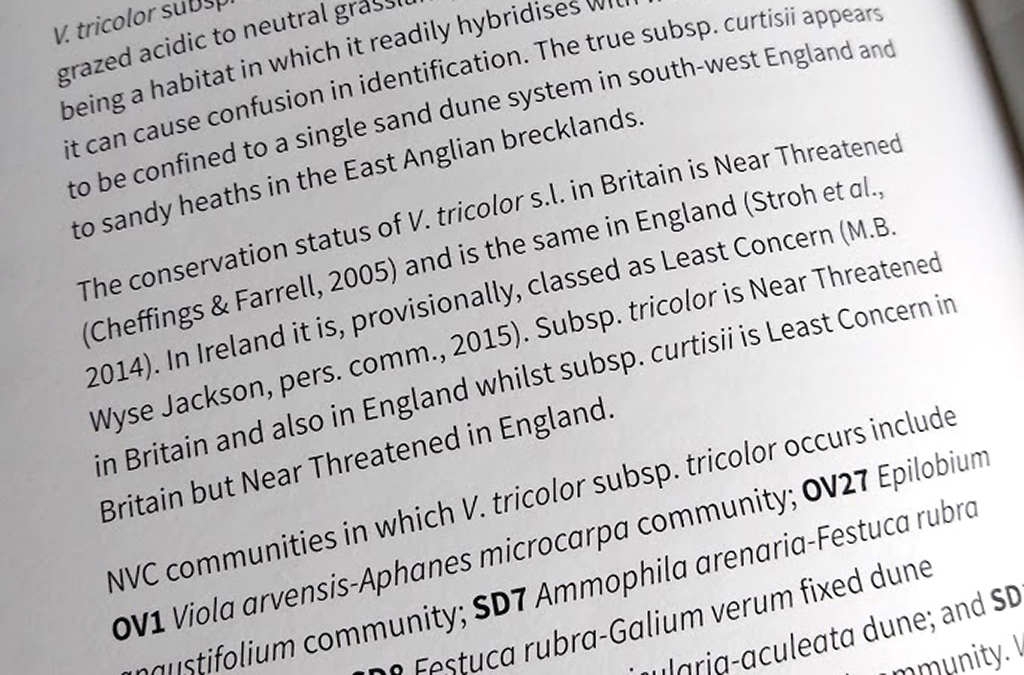

At the other extreme, many peer-reviewed papers go for very long paragraphs. See this example from PLOS ONE, which is by no means unusual in the scientific literature (excerpt below).

The mean paragraph length here is over ten times what it was in the BBC article. To be fair, this article is conveying vastly more information than the BBC piece, but that’s not the point really. The question is: how easy is it to read and understand the discussion?

For most readers, not very. And even if you’re fascinated by the topic, such long paragraphs are intimidating, and (unless very well written) pretty indigestible. It might take two or three reads of a paragraph to understand it all – and most readers are not going to be that patient.

So if you want to have any hope of appealing to a broader audience with your text, I’d recommend considering splitting up any paragraphs that are over about 180 words. This is especially true if the text has been typeset in narrow columns, where even a modest number of words can result in a solid block of text.

In conclusion

In this post, I hope I’ve conveyed some of the subtleties involved in structuring your paragraphs in complex technical writing, and how length can make a big difference to readability.

Of course, there’s so much more to cover in making your scientific writing engaging – from good sentence construction to making sure you’re not meandering off-topic – but being aware of the pitfalls of paragraph structure is a good start.