Complex B2B products: A more flexible approach to writing about features, advantages and benefits

The ‘feature–advantage–benefit’ (FAB) formula is a cornerstone of product marketing, but its inflexibility makes it difficult to apply to complex B2B products, especially in the scientific field. In this post, I’ll describe a more versatile way of thinking about FABs that makes it much easier to write well-targeted copy – without giving you a headache!

What are features, advantages and benefits?

Structuring a sales message using features, advantages and benefits is a tried-and-tested approach to selling. In my time as a copywriter I’ve certainly found it a useful way of analysing a product or service, and working out the points that will best engage the target audience.

But before we go any further, let’s define what we’re talking about:

- A feature is a matter-of-fact description of a distinctive attribute of the product or service. In B2B scientific copy, it often describes a product function that has been planned and executed.

- An advantage is an explanation of why the feature matters, preferably in terms that can be immediately understood by the customer.

- A benefit is an explanation of why a customer should care about the feature and advantage. It answers the question “What’s in it for me?”, in a way that addresses a problem the customer is facing.

To follow this ‘chain of logic’ from feature to benefit, you just need to know two words: “So what?”. When presented with a product attribute that you don’t understand, keep asking “so what?” until you get an answer that expresses why you should care.

In B2B scientific marketing, these ultimate benefits are typically one of the following:

- Saving money: Examples include reduced maintenance costs, or a cheaper consumables package.

- Saving time: This usually goes hand-in-hand with saving money, and is often fundamental enough to be viewed as a benefit in its own right.

- Increasing revenue: In the service sector, improved system throughput or software efficiencies often enable quicker turnaround.

- Improving performance: Improved specifications (such as sensitivity, reproducibility, or environmental robustness) may be important when the product is going head-to-head with a competitor.

- Improving versatility: This is a common benefit of modular systems that can be adapted to cover a wide range of applications.

- Achieving compliance: In some markets, showing that your system allows the customer to achieve compliance with regulations can aid sales.

- Reducing inconvenience: Examples include no-hassle product customisation, or easy-to-learn software.

- Offering peace-of-mind: Freedom from worry is another important benefit – the knowledge that you’re in safe hands if something goes wrong.

- Gaining a competitive advantage: Finally, if any of the above allow your product to achieve something that no competitors can do, that’s something worth highlighting.

The problem with FAB

So far, so good. But when applying this formula to complex products in the scientific B2B arena, I’ve come up against a problem: FAB on its own is too simple and inflexible.

Specifically, it doesn’t allow for additional steps in the F–A–B ‘chain of logic’, and it suggests that a single benefit will be equally relevant to all audiences.

I’ll demonstrate what I mean by an example closely based on real-life, involving a manufacturer selling an isotope-ratio mass spectrometer (let’s call it the X-Plus) to a service laboratory. Their literature says that the X-Plus has:

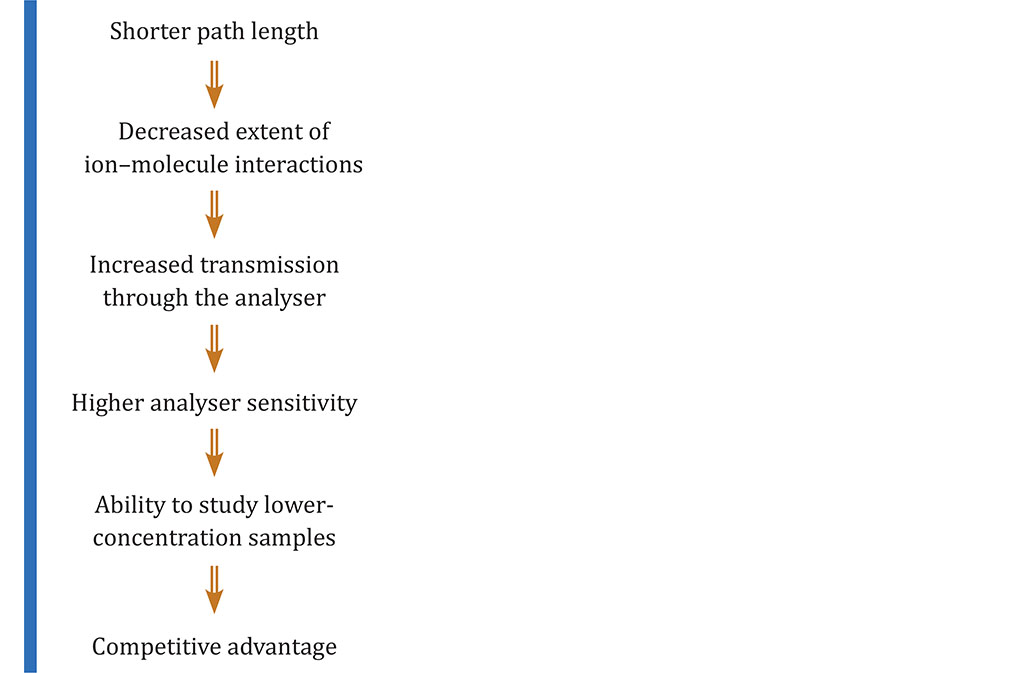

That’s fine so far – that shorter path length is clearly the distinctive feature. But then things get more complicated:

The company’s literature actually stops there. But, if we’re being rigorous about our FAB analysis, we should really follow it right through to the final benefit, like this:

That was a bit heavy-going, but we got there in the end – the last statement about the competitive advantage is clearly the ultimate benefit for the service laboratory. But what about all those extra bits – are those advantages or benefits? And isn’t this over-thinking it – do we really need to follow it through all the way? Do we even need to start with the technicalities about path length?

The answer to all these questions, I think, is that it depends on who you’re talking to, and I’ll demonstrate this below.

Considering the target audience

Let’s write the above example out again in a simplified list format, showing the ‘chain of logic’ we go through to get from the original feature to the ultimate benefit:

We now begin to see how we could construct a tailored marketing message, by considering the knowledge a particular audience already has, and the level of explanation that they’d be happy with.

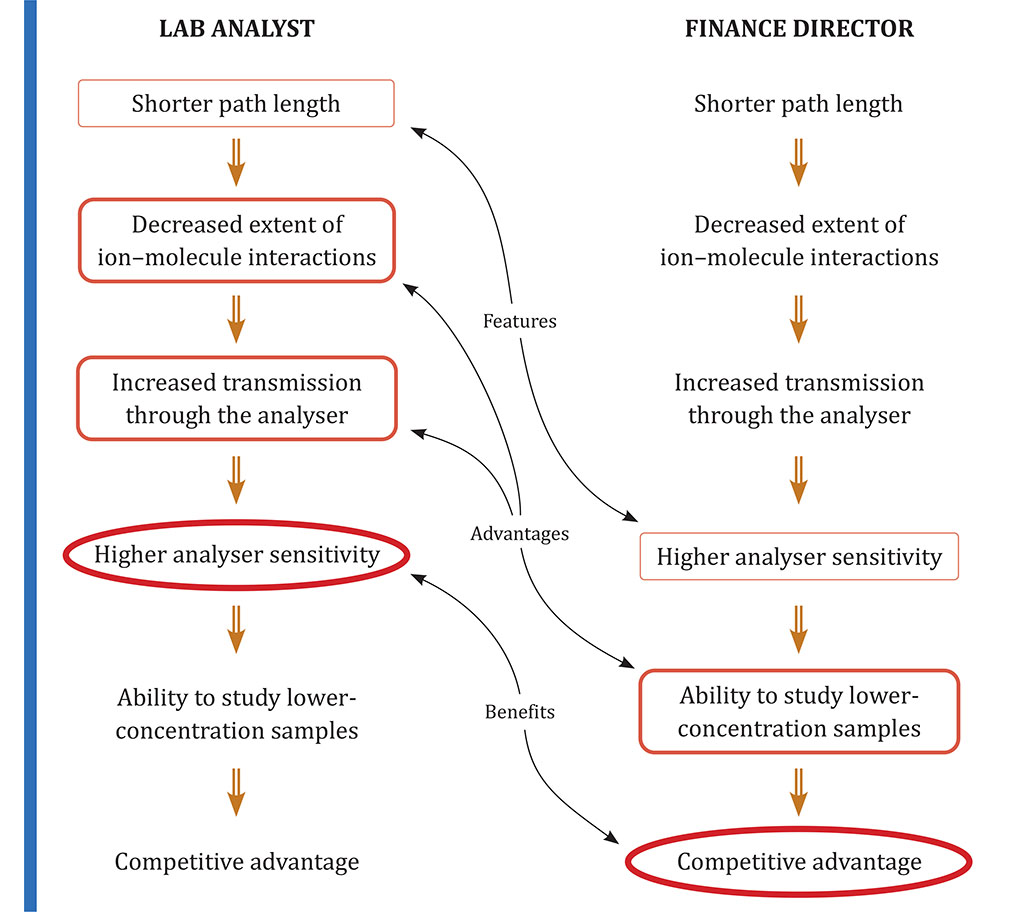

First, let’s consider an analyst using the equipment in a service laboratory. They’d almost certainly expect to be told about the shorter path length, because basing explanations on the fundamentals is a key aspect of appealing to scientifically-trained audiences. But on the other hand, they’d be perfectly happy for the explanation to conclude with a statement that the analyser sensitivity was higher. That’s the take-home benefit for them, and to go any further would be superfluous and possibly patronising.

On the other hand, if we want to appeal to someone in the company who isn’t so interested in the scientific aspects (let’s say the Finance Director), then we could trim down the physics bit, and instead lead with the point about the higher sensitivity. Following that, they certainly would be keen to hear about the competitive advantage that their business might gain, so we could finish with that as the take-home message.

To summarise all this, here’s that diagram again, annotated to show what we want to tell each person. Note that the feature, advantage(s) and benefit we’re going to use in our copy now depend on who we’re talking to!

Writing a tailored marketing message

Following on from this analysis, it’s now straightforward to write some text that is tailored to what each audience needs to hear.

So to the lab analyst we could say:

And to the Finance Director we could say:

Splitting and combining FABs

Performing the analysis in this way also makes it easier to merge and simplify aspects of the FAB-based explanation. This is important, because in scientific B2B marketing, it’s common for one benefit to stem from multiple features, and for one feature to have multiple benefits. Handling this complexity is essential to make marketing messages concise and understandable.

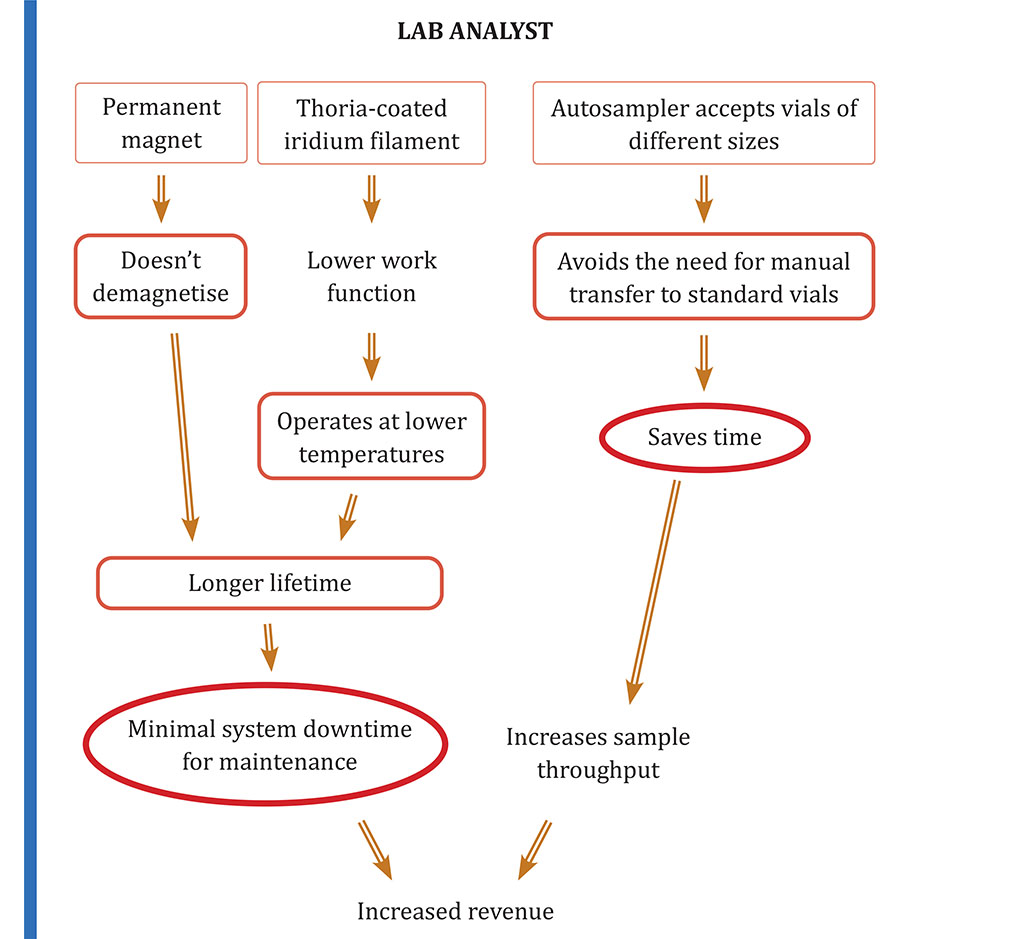

To illustrate this point, let’s look at three further features of the ‘X-Plus’ product, all of which ultimately contribute to increased revenue:

- A permanent magnet in the mass analyser

- A thoria-coated indium filament in the ion source

- An autosampler that can be configured to accept vials of different dimensions.

We’re now ready to perform the same analysis for our two audiences. First is the lab analyst, who needs the technical details, because they’ll be unconvinced if we gloss-over the fundamentals:

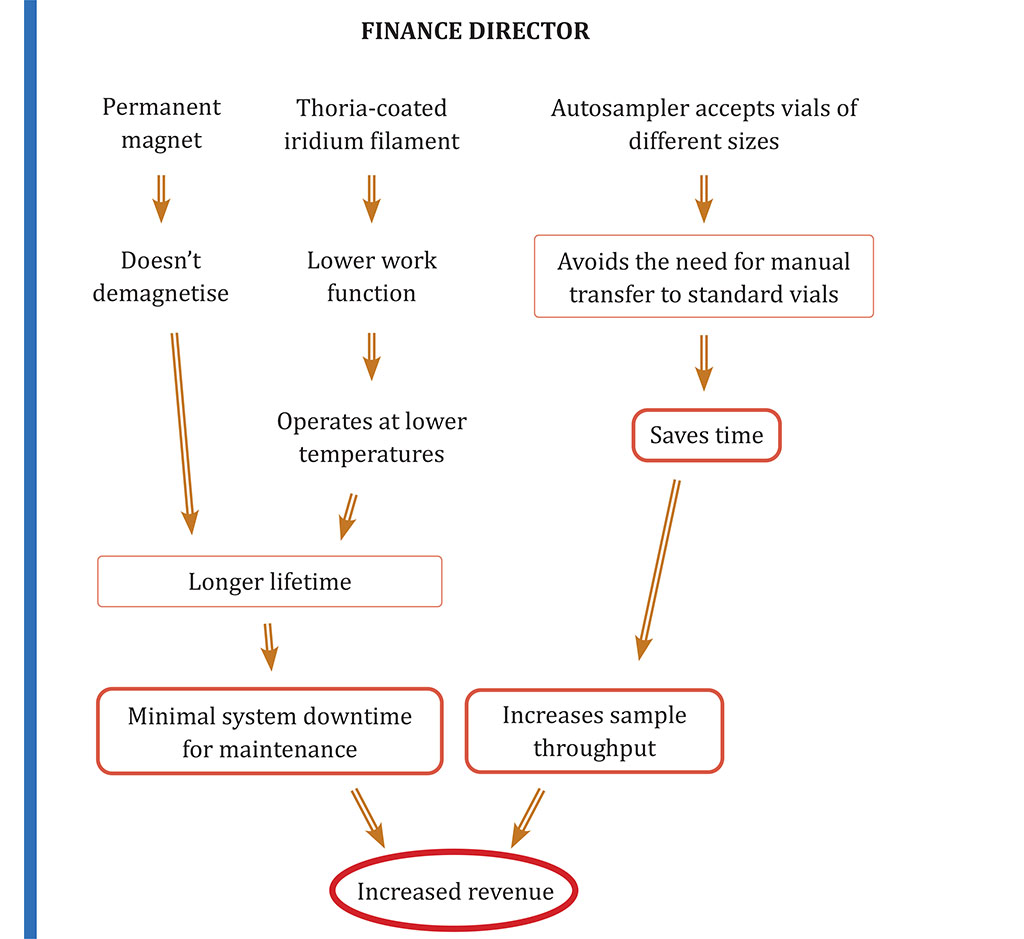

And now the Financial Director, who is primarily interested in the ultimate benefit, but still needs the explanation to be grounded in what the instrument provides:

Analysing the product like this allows us to see more clearly how we might construct our sales messages.

For the lab analyst, we might write:

Whereas for the Finance Director we might present this as:

Conclusion

FABs are a powerful way of analysing what will make a product appeal to an audience. But as I’ve shown here, the traditional structure involving a single feature, advantage and benefit doesn’t always work very well for complex technical products.

So I’ve presented here what I think is a more useful way of thinking about FABs, which:

- Accommodates multiple steps in the ‘chain of logic’ leading from the distinctive feature through to the ultimate benefit.

- Allows you to identify FAB messages that are tailored to individual audiences, all from one analysis.

- Allows you to see easily how to split and combine FABs, to develop text structures that concisely explain complex scenarios.

Clearly, where we’re writing copy that isn’t directly targeted at a particular audience (such as a product webpage), we need to make a judgement about where we start our argument, where we finish it, and how much weight we attach to each part of the explanation.

But look at what this more nuanced analysis has allowed us to do. By injecting a bit of flexibility into the FAB concept, it makes it much easier to think about feature-rich products with intersecting advantages/benefits, and develop clear messaging for different target audiences.