Citing your sources: The importance of references in B2B marketing literature

Establishing the reader’s trust in what you say is fundamental to all types of writing – and for science-focused B2B communications, including references is set to rise in importance as a way of achieving that. But what’s the best way of including this reference information in the text? Here, in the first of two blog posts on this topic, I provide some criteria for deciding on the best sources to include, and then summarise the three main ways of citing literature sources in different types of business communications.

The need for trust in scientific writing

In academic publications, it’s established practice to include references to your sources when reviewing the current state of a field of research. This is because it demonstrates the factual basis of what you’re saying, enables your statements to be checked, and so ‘oils the wheels’ of scientific discourse.

Up to now, such rigour has scarcely been necessary in business literature such as white papers and blog posts. But that may be about to change with the increasing use of AI-enabled tools to facilitate the generation of all sorts of scientific content. With their ability to create convincing-sounding but doubtfully accurate statements, over time readers may become less inclined to trust text summaries that appear to be over-generalised, or discussions that put forward surprising or contentious ideas with little justification.

Using referencing to establish authority and believability

The trouble is, being successful in scientific B2B marketing often does require summarising the current state of play, and then presenting a viewpoint that runs counter to established wisdom, or which puts forward a new idea. So how can we ensure that readers believe what we’re saying?

It’s my view that providing links to literature sources is going to become increasingly important for building this trust in science-focused B2B communications. I think this will add to the good reasons there already are for referencing your content, namely:

- Referencing is reassuring for scientifically-minded readers, by providing one of the things they’d expect in an academic paper.

- It can be helpful to both the reader and people in your organisation, especially if you’ve found sources of reliable information that aren’t behind a paywall.

- It shows that you’re knowledgeable about the literature, and hence the subject matter, providing an authority boost.

- It allows you to acknowledge the work of key people in the field – who may be current (or future) customers!

Of course, finding and compiling these sources of information, let alone working out how best to present them in the text, can be time-consuming. It’s also unlikely to be the highest priority when time is tight.

So in this blog post I’ll give a brief outline of the three main options there are when using referencing in commercial writing, and where they’re best employed, helping you to pick the best method for the purpose.

How to select the best references

But before we get into that, it’s worth making sure that the sources you choose are going to give you the authority boost you need.

Here are my thoughts on how to select your sources to ensure that they provide the best value in terms of the ‘trust factor’ for the reader:

- Peer-reviewed journals are often regarded as the ‘gold standard’ of scientific sources, although getting hold of the full text is often not so easy. But beware of articles in obscure regional or very niche journals, especially those that operate solely on an ‘author pays’ open-access model – they may not have such rigorous standards of peer-review.

- Trade-magazine articles can be very good for covering niche topics, but be mindful that industry-sponsored editorial content may present a biased viewpoint. Some websites can also be riddled with adverts, which can test the reader’s patience.

- Independent reports by international organisations or industry bodies can be valuable, but check who’s funded the report to ensure it’s going to be objective.

- Journalistic articles need to be approached with caution, as some may be biased by the agenda or profit-seeking motives of the parent organisation. Having said that, there are many outlets out there that can be relied upon to report science accurately – such as BBC News, New Scientist, Scientific American, Chemistry World, The Conversation and The Guardian.

- Standard methods – such as those released by ISO, ASTM, or one of the European standards organisations – are highly trusted, and worth citing if relevant to your discussion.

- Commercial content should not be completely discounted as worthy of referencing, so long as it’s not primarily product-focused. Industry-focused conference presentations, technical ‘how-to’ videos and subject-matter overviews can all contain valuable information.

- Avoid citing very old material, unless it’s important to establish the historical background or mention a particularly important paper in the field.

- Avoid citing crowd-sourced content. For example, Wikipedia is great as a starting point for your research, but citing it as a source in the final piece may indicate a lack of rigour in your fact-finding.

- Avoid citing heavily opinionated pieces – Getting scientific readers to trust what you’re saying requires balance in putting across your viewpoint, so make sure that your sources also meet a high standard of objectivity, and watch out for ill-considered opinion pieces.

Now we’ve covered that, let’s get into our three referencing options.

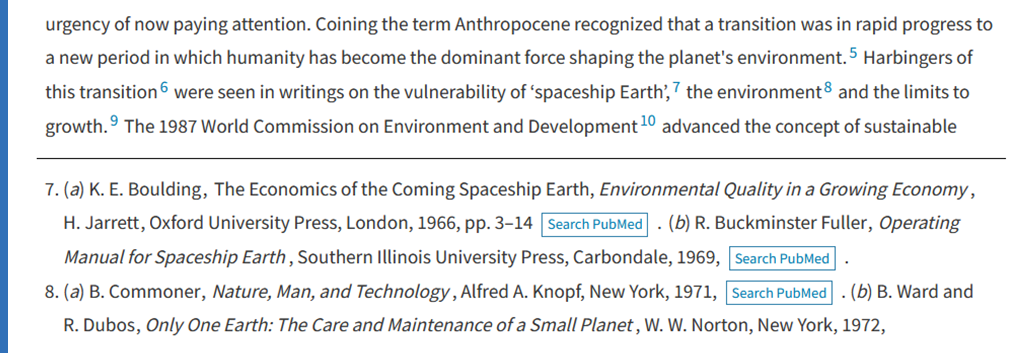

Referencing option 1 – In-text citation & endnote reference

This is the familiar method of referencing in science, consisting of two parts:

- An in-text citation: This is a number or a short bit of text at the end of a clause or sentence, which indicates what a reference applies to.

- An endnote reference: This is placed at the end of the article, but an alternative is to put them at the bottom of the page where they’re first cited (this is called ‘footnote referencing’). Either way, it contains information about the source itself – such as the author, journal name, and year.

There are many options for presenting each of these, and I’ll discuss these in the next blog post. But to generalise for the moment:

ADVANTAGES:

- It’s versatile – there are styles to suit all purposes and preferences.

- This method is supported using word-processing packages such as Word and GoogleDocs.

- It’s readily scalable, although how easy this is depends on the exact format you choose.

- The information about the source is permanently stored as text within the article.

DISADVANTAGES:

- The use of in-text citations disconnects the statement in the text from the reference, reducing the likelihood that readers will bother to take a look.

- Setting up the citation scheme can be labour-intensive if you don’t use your word-processing package to (semi-)automate it.

Because of their suitability for supporting and providing evidence for statements made, I think this method is best for formal documents expected to have a long lifetime – such as white papers, industry reports, trade-magazine articles and conference posters.

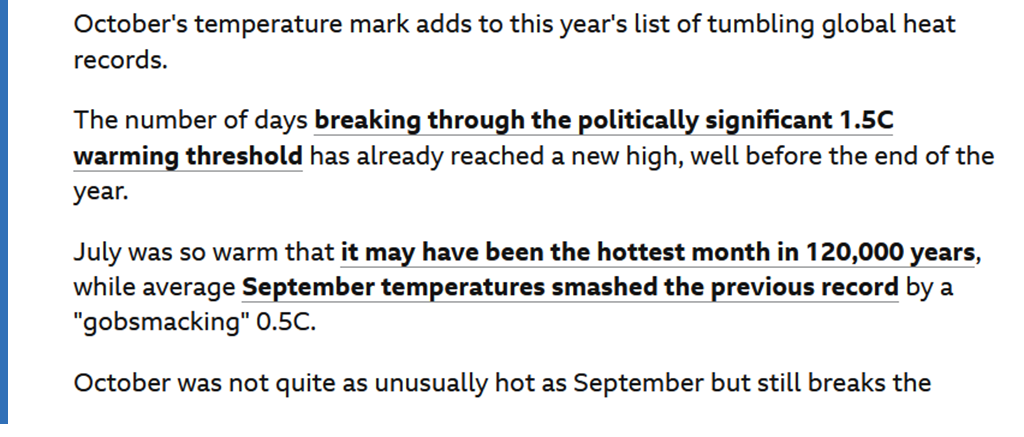

Referencing option 2 – In-line linking

Although not a conventional method in academia, in-line links to external sources (known in the marketing world as ‘outbound links’) definitely have their place as a method of citation for science-focused communications.

ADVANTAGES:

- Easy to implement – just highlight and hyperlink.

- Eliminates the need for fussy-looking citations and reference sections.

- Has the potential to improve site authority and SEO, especially if you link out to high-authority sources.

- Makes the link-out obvious to the reader, and increases the chance that they’ll follow it.

DISADVANTAGES:

- Requires that a direct link to the source exists (which may be difficult for things like conference posters).

- It can be all too easy to break the links during the process of getting your content online.

- The anchor text (which is used to contain the hyperlink) will need writing carefully so that it clearly lays out what the source said – which in science can make for long and convoluted statements.

- It quickly becomes very distracting to the reader if you have more than a light scattering of links.

- If the link gets broken, then information about the source may be permanently lost (in addition to which, having broken links can harm SEO).

Based on these substantial disadvantages, I think this method is best for online content with a limited lifetime, or which is regularly reviewed – such as news releases, blog posts, and product/application pages.

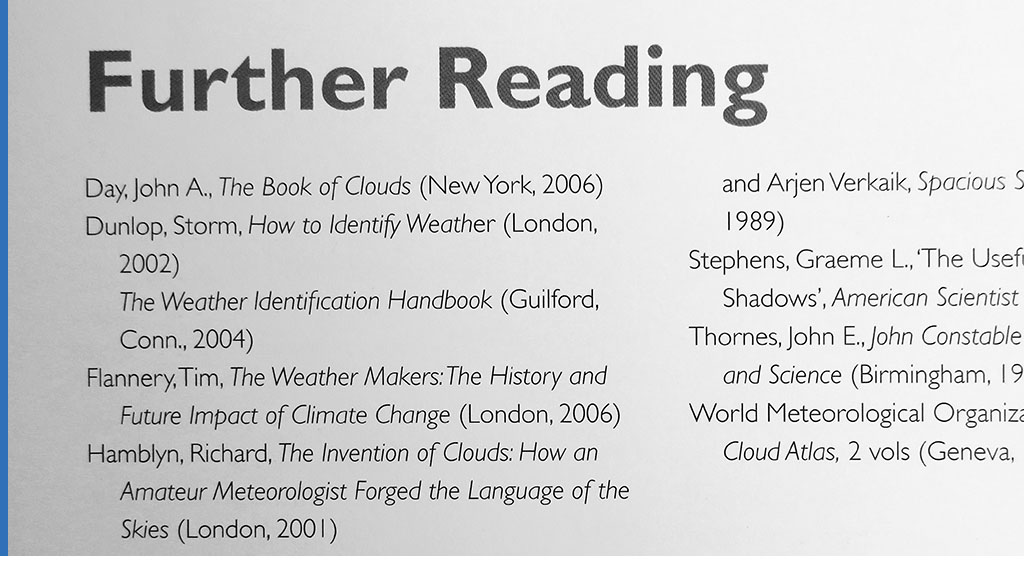

Referencing option 3 – Bibliographies

A bibliography is a list of sources that was useful in putting together a piece of writing, or which you think will be useful to the reader, but which doesn’t directly relate to any particular statements in the main text.

ADVANTAGES:

- Shows that you’ve done your research, without having to put citations against every single fact.

- Easy to put together – just compile the list as you go along.

- Makes it easy to add commentary on why the source might be useful to the reader.

DISADVANTAGES:

- Makes it very difficult for the reader to trace the origin of a particular statement, and so is unsuitable for building credibility around potentially controversial findings.

As a result of the disadvantage mentioned above, I think this method is best for review articles, where you might need to establish the factual basis of a piece, but where the facts themselves are likely to be widely accepted and believed.

Bibliographies also have a place in customer case-studies, where it can be a nice touch to provide a list of papers the customer has published that relate to the work described (as ‘Further reading’).

Conclusion – Using references for establishing authority

References have long played a vital role in scientific communication, although up to now their importance in B2B communications has been less critical. However, that seems likely to change as the emergence of AI-based tools for researching and generating content lead to readers becoming more wary of generalised statements and unsupported claims.

To ensure that your readers continue to have trust in your communications, I think it’s worthwhile not just to find good-quality sources, but to reference them in the way that’s most effective for the purpose. By doing this, you’ll help to build authority and believability around what you’re saying, as well as making it easier for readers to find out more about a topic, should they wish.

Ready to start referencing? Read my next blog post for details of my tried-and-tested method for citing your sources simply and clearly… or get in touch.